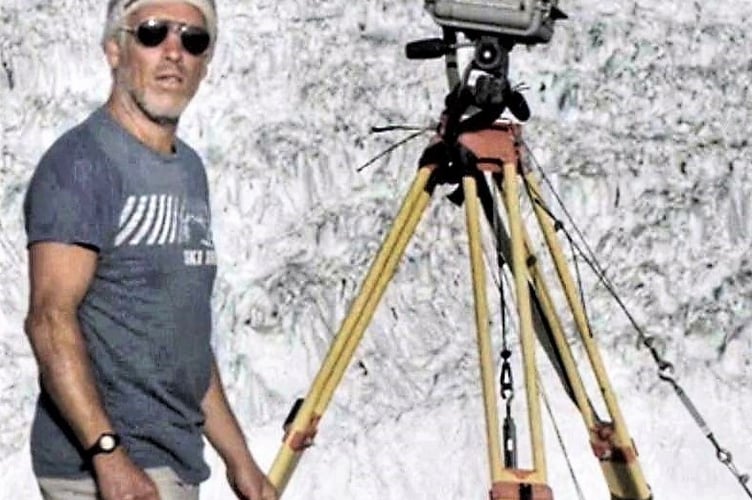

Professor Alun Lloyd Hubbard has had an amazing life.

It began in the tiny coastal village of Borth, but it took him to Bali, the Alps, Patagonia, Greenland and Peru – and right now sees him writing a book on a Spanish beach.

This week the Professor in Glaciology at The Arctic University of Norway will join global leaders and scientists at Sharm El Sheikh in Egypt for a particularly momentous COP27 climate summit.

And a fortnight ago he featured in the BBC’s flagship documentary Frozen Planet II – in an episode viewed more than 12 million times in the UK.

Not bad for a boy from Borth – and he had lots to say about his childhood home, its future and how it inspired him during an interview with the Cambrian News.

In his later life – following his studies at Oxford and Edinburgh universities – he has become an acclaimed glaciologist and field scientist.

He also also been recognised for quality of his teaching at Aberystwyth University.

His years of observing the rate of change in the earth’s climate, and modelling the outcome of these changes from glacial melt, have seen him go from optimism to cynicism – and back again.

He grew up in The Friendship Inn on Borth high street and reminisced fondly about the sandy beaches, misty mountains and sprawling countryside of Ceredigion.

He says he has always had an indelible connection to the natural world due to his upbringing.

“I feel very fortunate to have grown up there. It’s slightly end of the line but quite an amazing, unique place,” Professor Hubbard said of the village of his birth.

“My career has always been tied up with mid Wales and as a result I’m very drawn to places where the mountains meet the sea.

“In many ways you’d say I had a privileged childhood because I always had complete freedom to roam and explore at my own content.

“I used to go truant at school, nick a bike and disappear for a couple of days at a time.

“It was a different time then.”

He spoke fondly of his adventures, his inspiring Scout leader Dr Andrew Agnew – a botanist and conservationist from Aberystwyth university – and the days spent being in and observing nature.

But when asked about Borth’s future, he said: “Alas it is only a temporary coastal feature.

“It came in a storm and it will disappear in a storm.

“When I was growing up in the 1970s, Borth was flooded pretty regularly.

“In fact, one of my overwhelming memories is watching all my toys disappearing down the main street.

“The house was often completely smashed in.”

He raised the plight of villagers in ‘decommissioned’ Fairbourne, further north along the coast, where Gwynedd County Council confirmed in 2016 it will do no more to save it from the sea.

“The storms have started up again now and are only going to get worse,” he said.

“And already, I know because my parents (in Borth) bemoan it, the insurance premiums are going up – even without us making a claim.

“But if you live in a flood zone this is what’s going to happen, so the process is real.

“Borth is very susceptible to those south westerly winds that bring floods that totally trash the village.

“The Greenpeace term for it – the decommissioning of coastal communities – it’s very real.”

He was quick to emphasise the connection between the work he does and the fate of coastal communities around the world, mostly in places a long way from Borth or Fairbourne mind you.

He echoed the words of much-adored wildlife filmmaker Sir David Attenborough at COP26 last year, that it is those who have not caused these problems who are paying the highest price.

After moving from Penglais School in Aberystwyth and learning ‘discipline’ at Christ College Brecon boarding school, he was accepted to study at the University of Oxford.

He did not speak highly of his political contemporaries as an Oxford student - many having now served in Government and even as Prime Ministers.

He said they were as unpleasant then as they are now.

He found his passion studying political geography, eventually graduating university with a first class honours – writing an award-winning dissertation about Cadair Idris mountain in Meirionnydd.

For the next three years he worked a bit, surfed a lot, taught English as a foreign language, became a diving instructor in Bali, and fought off any instinct he had to grow up.

That was until he saw the University of Edinburgh offering a PhD researching glaciers in Patagonia and Peru.

“The hardest decision I ever made was to leave Bali and travel to Edinburgh mid-winter,” he said.

“But it was probably one of the best decisions I ever made – following my heart.

“I knew I was never going to make big money out of doing it but I ended up having a life that was satisfying and rewarding.

“The PhD took me to the Alps and then to Patagonia – I couldn’t have designed a better course.

“Well... I suppose I could have been doing fieldwork in the Amazon with the Brazilian beach volleyball team, but it was magic.

“My thesis was about modelling the response of glaciers to climate change.

“And this was back in the 90s before climate change was a thing.

“I was quite numerate and into computing and I was trying to produce new code to be able to model glaciers accurately to climate response.”

But he was quick to add that modelling was no panacea, and he soon learned it has limitations.

He said they are relied on too heavily and, in many cases, fail to convey the disastrous rate of climate breakdown.

“I think that’s probably been a strong theme in my career: we need real measurements to get a real handle on what’s happening, rather than just modelling it,” Professor Hubbard continued.

“Models are too clunky, too slow and too sluggish to keep up with very high rates of change in very short amounts of time.”

He gave the example of modelling by British universities used to justify ‘herd immunity’ as a response to the Covid pandemic.

After huge criticism the Government saw out a screeching U-turn and change in strategy.

“You’re playing with numbers and you let it run its course but then you realise our hospitals are going to be overwhelmed and people are going to be dying left, right and centre,” he continued.

“Who’s to say what was going through Boris Johnson’s or Matt Hancock’s mind at the time - probably nothing!”

He returned to the significance of modelling to climate research, and the need for accuracy.

“By the mid 90s the second IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report was out and the models were dreadful – so we had no idea about the size of the problem we were facing,” he said.

“What I’ve observed in Patagonia, Greenland, and the Alps is that things are happening far faster and at a much higher magnitude than forecasts are predicting.

“Which ultimately relates to sea level rises and the fates of Borth and Fairbourne!

“And we’re looking at that from just the Greenland ice sheet - and what I see in terms of the rate of change, in the 20 or so years I’ve been there, is flabbergasting.

“This summer I went back to do some work on the glacier that I worked at in the Alps for my PhD, and it’s gone...

“That was something we joked about. It was our worst case, nightmare scenario – that it could be gone within the century.

“But it’s gone within 20 or 30 years. It’s gone in my daughter’s life time – not just my lifetime.”

But Professor Hubbard said lots of things have given him hope, including Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, young people holding the older generations to account and the slow but steady change of behaviour by financial institutions.

He describes himself as ‘a traditional socialist’ and a subversive but says he is prepared to be more conservative to influence the millions of Brits who read the Daily Mail.

He is adamant people in his position can no longer be content appealing to Guardian readers and ‘preaching to the converted’ - nor is it any use, he says, appearing smugly superior.

The challenge is trying to persuade people - particularly those, like his mum, who read right-wing British newspapers - that change is needed.

Another source of hope and inspiration, he says, was being part of Frozen Planet II. He is no stranger to documentary making and was involved in the first series too.

But he said it was a privilege to appear alongside ‘Saint David’ - Sir David Attenborough – and that the documentary was an ‘optimistic call to arms’, with a strong message.

He hailed the ‘watershed’ moment over the last five years that has seen nature documentaries become bolder about the narrative on the climate emergency.

Addressing the readers of the Cambrian News, he said: “Climate change is happening. It’s real.

“Most of the changes are happening a long way away from the coast of Wales but it is affecting us.

“We’ll have more severe drought, more intense storms and of course this inevitable sea level rise which will threaten coastal areas.

“The big storms will become severe and will happen more frequently – that is a disaster for an area that is predominantly reliant on agriculture and tourism.”

In the days since the interview, he was offered the chance to attend COP27 to support the UK’s climate delegation.

When asked days before about the conference and what he would say if got the chance to attend, he told us he would: “Point fingers at politicians and business leaders and say, however much solving these problems are about grassroots action, there are parts of the world where the politics are just not functioning.

“Grasp the big picture and get on with it,” he said.

The Cambrian News will be watching closely to see if he delivers this message.

UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres told international media on Friday that, without an historic climate pact, we will be ‘doomed.’

So the stakes couldn’t be higher.

.png?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.