You can imagine that when Dr Peter Jones was a child, he’d be the one jumping into puddles and getting as mucky as he could. It’s not as if there were many bogs around Epsom — the going would be too soft for the racehorses — but somehow, after studying apes and the like in their natural habitats, or protecting them at Bristol Zoo, he has found his way to mid Wales. And he couldn’t be happier than a kid in mud.

“Look at the way the water is being held back,” he tells Cambrian News. “The sphagnum is really getting a chance to grow. This is exactly what we were hoping for here.”

‘Here’ is up in the expanses of the Dwyi forest deep in the Cambrian Mountains, about 5 miles as the Red Kites fly from Strata Florida. The Dwyi forest site is run by Natural Resource Wales.

Sphagnum mosses can hold more than eight times their own weight in water and help keep the bog wet and spongy.

It’s 33°C, there isn’t a cloud in the sky, and Dr Jones is wading over acres of soft peatland studying the series of miniature berms — “bunds” — he has engineered to slow and stop as much water as possible flowing down into the valleys below. And it’s all about getting the sphagnum to take and grow.

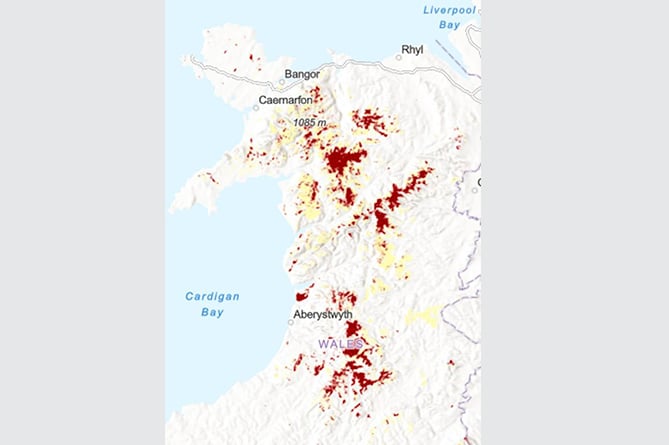

Right now, about four per cent of Wales is covered by peatland. NRW says that about another 10 per cent of our Welsh countryside is peatland that has been modified by one means or another — drainage, erosion, afforestation, nutrient pollution, under-grazing or over-grazing often coupled with lack of management, and problematic native or non-native species.

But while small, bogs have a big role to play in fighting climate change, storing carbon and slowing down water courses to ease flooding further down river. Yes, peatland is a huge sponge.

NRW is working with bodies such as Snowdonia National Park, the National Trust, the RSPB, Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority, Radnorshire Wildlife Trust, North Wales Wildlife Trust, Coetir Anian, Clwydian Range AONB, and Wye Valley AONB to protest and enhance these bogs. It works with landowners, through land management agreements to make a difference in places like Cors y Sarnau, Waen Rydd and at the Brecon Beacons SSSI, on the Anglesey fens, or working across the border into England at sites at Fenn’s and Whixhall.

A recent report from NRW highlights how work by specialists such as Dr Jones and his colleagues at the Peatland National Action Programme is restoring the degraded bogs of Wales at a record pace.

Bogs are an unlikely hero where health is essential for water security — even more so now given that a drought has been declared for much of south-west Wales, the rest of Wales has had rainfall levels far below average, and our natural environment is feeling the effects of more severe weather conditions more regularly.

The report says the Welsh Government’s annual target to restore 650 hectares of peatland was surpassed by restoration action on over 1,000 hectares, the equivalent of 1,400 football pitches.

Given that 70 per cent of the UK’s drinking water comes from upland areas dominated by peatlands, the need for their restoration is clear following a month [July] where Wales has received only 56 per cent of its expected rainfall.

What’s more, wet bogs contain up to 90 per cent water — meaning they act as a natural barrier to spreading wildfires and reduce the risk of floods further downstream.

They are also an incredibly efficient carbon store, retaining more carbon in the soil than the equivalent capacity of a forest of trees. That four per cent of Wales covered by peat stores up to 30 per cent of Wales’ soil carbon. However, damaged peatlands are releasing this carbon into the atmosphere, contributing to speeding up climate change.

As droughts, wildfires and floods are predicted to exacerbate in the coming years, Welsh Government set up the NPAP after recognising the essential role peatlands play in fighting the climate and nature emergencies.

Julie James, Minister for Climate Change, said: “Bogs might not sound very glamorous, but they are Wales’ unsung heroes – especially during prolonged periods of dry or wet weather, like we have seen recently.

“When peat bogs are in a good state of repair, they are our most efficient terrestrial carbon sinks; they are home to a wide range of wildlife and plants, and even help purify our drinking and bathing water.

“Their restoration is vital to our response to the nature and climate emergencies so this report by NRW is very welcome news and I want to thank them for their hard work in accelerating their efforts to beat the target.”

Leading the fight to save our bogs is Dr Rhoswen Leonard, the project manager for the action programme.

“Our success in delivering restoration activity on over 1,000 hectares of peatland in a year reflects the collective passion of the NPAP team and our partners to achieve high-nature, low-carbon targets for the benefit of the people of Wales,” she said.

“In support, Welsh Government inspires the urgency, and Natural Resources Wales and our partners provide the momentum and joined-up capacity to make this programme a success.

“Peatland restoration is a big growth area to address the climate and nature emergencies, so we’re very grateful to our partners, for their impressive successes in rewetting peat, and to the innovative contractors who adapted techniques and equipment to address the challenges on site.”

Rewetting peatland is a comparatively simple solution to both increase carbon storage and re-establish biodiversity, as habitats are restored for mosses, insects, birds, and other creatures to thrive. Farmers play an important role in peatland restoration as they help identify the breeds, often traditional breeds, that thrive best on restored peatland and, through discussion with ecologists, establish the best stock rate for different seasons.

The aim is to restore the natural water levels by using various techniques such as contour bunding and peat dams to block historic drainage ditches. NPAP has identified more than 100 different techniques to improve peatland condition.

Wet bogs and fens don’t burn easily and only superficially if they do. However, on drained and dry sites, surface vegetation fire can ignite the peat, a natural fuel, resulting in deep smouldering fires. These fires are difficult to extinguish and can go on for weeks, releasing a devastating amount of carbon.

Healthy peat contains up to 90 per cent water. It’s a natural flood mitigator, as its impressive water-retention capacity allows for a more gradual water release in our landscape. Sphagnum moss is key to the water retention and formation of peat. It can hold up to 20 times its mass in water and its slow decomposition under waterlogged conditions forms dark brown peat soils. A meter depth of peat represents a millennium of peat accumulation.

Water derived from healthy peatlands is high in quality and low in pollutants and nutrients, allowing for more effective water treatment Peat restoration is important for water security because healthy rewetted peatland helps sustain baseflow to river and stream headwaters during periods of drought and subsequent low flows.

But it’s not just boglands in small mountain valleys that are key. NPAP is also restoring so-called ‘raised bogs’.

Raised bogs get their name because of their domed shape. They are areas of peat that have built up over 12,000 years and can be as deep as 12 metres. They are home to rare plants and animals such as the rosy marsh moth caterpillar and the iconic bog rosemary.

Raised bogs are one of Wales’ rarest and most important habitats and, because of their environmental interest and importance, they are designated Special Areas of Conservation (SACs).

Wales is home to only 50 raised bog sites, and these have suffered more habitat loss than any other peatland type and remain under acute pressure. Only seven of the sites in Wales are designated as SAC, and these represent over 10 per cent of the UK SAC resource of raised bogs.

Healthy peatland and raised bogs in good condition absorb carbon from the atmosphere which means they are important in the fight against climate change. If raised bogs are not in good condition, they release harmful carbon into the atmosphere.

Right now, NPAP is working on seven raised bogs in Wales: Cors Caron in Tregaron; Cors Fochno in Borth; Cors Goch in Trawsfynydd; Rhos Goch in Builth Wells; Waun Ddu in Crickhowell; Cernydd Carmel in Cross Hands; and Esgyrn Bottom in Fishguard.

The sites have suffered due to poor wetland management in the past and this has caused invasive plants to take over, and crowd out important plants like sphagnum mosses.

Raised bogs provide multiple benefits to the environment, wildlife and people. They are home to rare plants and wildlife, they store carbon from the atmosphere, can store and purify water and they also provide a fascinating insight into our environmental history.

They are also great places for people to visit and enjoy nature at its best.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.