“Why do we give animals a better ending than we give ourselves?”

This is the question Mary (pseudonym) asks as an assisted dying bill continues its progress through Westminster.

The bill will affect Mary more than some – living with a brain tumour which will eventually become terminal, she thinks about death a lot.

Mary chose anonymity for the sake of her school-age child but wants people to consider her situation when trying to wrap their heads around this historic bill.

The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill would allow terminally ill adults with six months or less to live to end their lives with the assistance of a medical professional.

In June the bill passed its biggest parliamentary hurdle - its third reading in the House of Commons - and is already due for its second reading in the House of Lords.

With Lords generally being reluctant to block bills from an elected member of parliament, in this case MP Kim Leadbeater, and BBC analysis suggesting most Lords are in favour of the bill, it is increasingly likely to become law and if so, by as early as 2029.

But is Wales ready for a law legalising assisted death?

Mary says because of the lack of hospices in north Powys, she is considering an assisted death when her time comes.

Being cared for at home might not be an option for her, so a hospice close to her loved ones would be her ideal setup.

But with her closest hospice being an hour’s drive away, she doesn’t see that as feasible for her family to visit her regularly.

She said: “I’ve had therapy and spent a long time contemplating death.

“Choosing how you die is an absolute fundamental right.

"My final two years will be horrific.

“I will have seizures and could experience severe personality changes – it would be horrible to die angry, and I don’t want my child to see that.

“I don’t want to die with half a personality sitting in my own [faeces].

“I like the idea of having a living wake where all your favourite people come – why would I want to miss that?

“It would be fun to plan and have a loving exit.

“I like the idea of being in control of the timing and not having a painful, humiliating exit.

“If palliative care [here] was perfect, then the choice would become harder.”

This is what the main opponents to the bill say – that hospice and palliative care in the UK is not good enough to offer patients a real option, with Westminster Health Secretary Wes Streeting fearing that people would feel “coerced” into an assisted death simply because the palliative care that should be there, isn’t.

At the moment, people in Wales are being failed in palliative care (the care you receive to manage pain and other symptoms during serious or life-threatening illnesses).

Palliative care staff report patients dying in A&E and in corridors because of the lack of planned management of their pain and symptoms.

In 2024, end of life charity Marie Curie published the report from Wales’ largest-ever national post-bereavement survey, finding that too many people are dying in pain, without the care and support patients and families needed.

Common problems faced included accessing medicine out of hours and high use of emergency care, suggesting a lack of adequate in-community support to manage their symptoms and a lack of ability to plan – 46 per cent of those who died in hospital had no family present.

Those surveyed reported that healthcare staff did not have enough time to provide adequate care for dying people, with one in four people who passed away probably or definitely not knowing that they might die due to their illness – one in three respondents said healthcare professionals hadn’t discussed death and dying with the person who died.

This is another concern raised by the bill – who and how the assisted death will be administered.

The bill would permit but not require medical practitioners to discuss options including assisted deaths, with their patients at an appropriate time, whilst there would be strict rules against advertisement.

Another question would be who gets to decide when the patient has six months to live - a position Mary is anxious not to put her doctor in.

One NHS doctor in Ceredigion said she couldn’t be part of that decision-making process for her patients, given the current state of palliative care.

Doctor Jones (pseudonym) said: “What a horrible power to be given, but also maybe a gift?

“Human doctors make mistakes all the time, so that’s terrifying.

“I personally think I would have to step aside.

“It would take a huge amount of resilience, confidence and expertise to be the team at the forefront of making these decisions.”

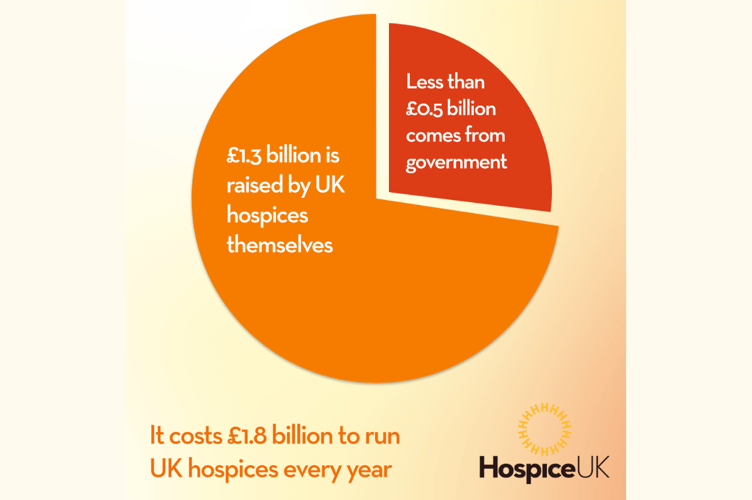

Despite the Welsh government giving £8m to palliative care in the last two years, hospices are still majority funded by donations – across hospices in the UK, £1.3 billion is fundraised yearly, with £0.5 billion coming from government.

There also appears to be no hospices in Ceredigion – though contrary to popular belief, most hospice care is done in the community, which is a service offered in the county.

Baroness Molly Meacher, who previously tabled an assisted dying bill, said she wants any new legislation to be accompanied by more investment in palliative care.

Dr Jones said the disparity in access to palliative care for people is a concern: “Morally and philosophically, I’m all for [assisted dying].

“Politically and practically, I’m not ready to get fully behind it.

“Equity of care in Ceredigion alone is an issue – people can’t get appointments because we don’t have certain specialities in certain areas.

“Access is so poor, it seems like the wrong thing to push through right now, but I recognise that people are having horrendous experiences with suffering.

“We are far away from palliative care being optimised – I think everyone who wanted a hospice bed should have one before implementing laws like this.

“The 2012 Health and Social Care Act and the following years of austerity have created such a climate of increased poverty and suffering, and a lot less access to high-quality care – it makes me nervous about pushing through a bill like this at pace.

“I’ve seen amazing hospices and I don’t think people know that they can exist.”

Having started her career as a carer, she worked with a patient with spinal muscular atrophy who she described as a “huge campaigner” against assisted dying laws.

She then cared for a man with multiple sclerosis (MS) who asked her to “kill me” - her experiences making a law like this “hard to reconcile”.

Assisted dying in Wales

Assisted dying becoming law in Wales would be tricky.

The bill would only affect England and Wales, though Scotland is currently moving a similar bill through its parliament.

Plaid Cymru Westminster leader Liz Saville-Roberts described the move to not give the Senedd its own vote on this, “regrettable”.

Saville-Roberts, MP for Dwyfor Meirionnydd, explained: “Health is devolved, and I firmly believe the Senedd must take responsibility for the services available to people at the end of their lives.

“I am concerned that we could face a situation where assisted dying is permitted only through the private sector in Wales.

“I am also disappointed that no Welsh MP was called to speak in the third reading debate.

“Scottish and Northern Irish MPs were given the opportunity to contribute, despite the bill not extending to those jurisdictions.

“I am nevertheless pleased that this bill has passed its third reading.

“We are a step closer to granting people dying of terminal illnesses dignity at the end of their lives, and the safeguards have been strengthened to protect vulnerable people.”

The bill does not yet specify how an assisted death would be offered – whether through the NHS or via a separate service.

It requires the person seeking the death to have the mental capacity to make the decision to end their own life, “a clear, settled and informed wish to end their own life”, and “is making the declaration voluntarily and has not been coerced or pressured by any other person into making it”.

The bill dropped in popularity with MPs after a clause was removed requiring a judge to approve applications for an assisted death – current criteria includes two independent medical professionals who judge mental, physical and social readiness (assessing for signs of coercion etc.), followed by a panel of experts, and two ‘periods of reflection’ having expired.

These are proposed as one week initially, followed by 14 days after panel approval, unless the progression of the disease requires this second period to be shortened.

It gives Welsh Ministers the option to make provisions for voluntary assisted dying services (VAD) in Wales, which may otherwise be made by the Westminster Secretary of State.

The bill allows a nominated medical practitioner to “prepare an approved substance for self-administration by that person and assist that person to ingest or otherwise self-administer the substance”.

This can also include “preparing a device which will enable that person to self-administer an approved substance” to end their life.

Incurable suffering

Some campaigners of assisted dying laws aren’t supportive of the current bill, suggesting it doesn’t go “far enough” - arguing that the bill gives people who already have limited time on this Earth a way out, whilst leaving others whose conditions aren’t terminal but who endure “incurable suffering” with few options.

One vocal campaigner for a law that included chronic illnesses was Louisa Eastland from Llanegryn in Gwynedd.

The Cambrian News spoke to Louisa, who had secondary progressive MS, at length in 2022 about her “right to die”.

Like most people, Louisa wanted to die in her own home with her loved ones surrounding her.

Instead, last October at age 54, she made one final trip to the Dignitas clinic in Switzerland for an assisted death.

In a documentary made about her final few months, Louisa is filmed saying: “I should be able to die in this country when I’m more ill.

“I could put up with more of this if I knew I could die here.

“But because I have to get myself to Switzerland, I have to go now...

“We all want to get rid of this illness, but in order to get rid of this illness, I have to get rid of me.

“I need to go to Dignitas – that's it.

“That’s the only way I can die.”

Family are restricted from accompanying loved ones to Switzerland because of the current suicide laws in the UK, or risk facing a police investigation and potentially up to 14 years in prison if found guilty of assisting a suicide.

Louisa felt so passionate about her right to die that she asked Ewan Atkinson, a film-maker, to create a film about her final act.

Ewan said: “Working with Louisa was a juxtaposition between one of the most beautiful and lucky experiences of my life, whilst being one of the hardest and saddest things I’ve ever worked on.

“She was so funny, so strong-willed – people talk of assisted dying as when people ‘give up’.

“You’ll see in the film it’s the opposite for Louisa.

“It was Louisa’s last stand against 35 years of living with MS, her way of taking control and saying, ‘I’m choosing when I want to be done’.

“Seeing through all the pain, stress and uncertainty Louisa went through with having a death abroad has highlighted to me just how traumatic an experience it is to have to go to a country you’ve never been before to die, when she wanted to do it in her garden.”

Ewan describes the film, One Way, as an observational documentary, portraying “the reality” of Louisa’s final few months: “You can only appreciate why Louisa and people like her should have an assisted death after seeing their stories – it stops being an abstract concept.”

Ewan and his team are fundraising to help finish Louisa’s film – to donate or find out more about the documentary, email [email protected]

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.