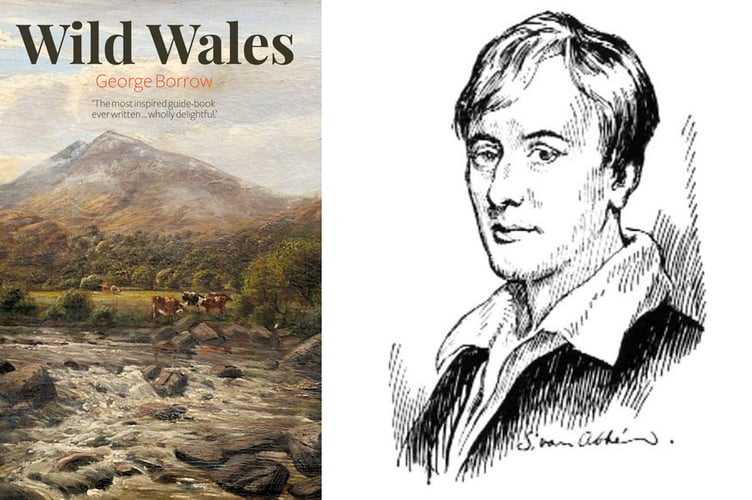

It’s 160 years since George Borrow published his great travelogue, Wild Wales, a book that brought the beauty of Wales to Victorians. Julie McNicholls Vale explores a new edition of the book that first put Wales on the map for tourists...

THIS year marks the 160th anniversary of the publication of George Borrow’s Wild Wales.

The classic travel book that takes readers on a wonderful journey through Cambrian News country and beyond has rarely been out of print since, and Gwasg Carreg Gwalch published a new edition in January.

The back of the cover of the book uses quotes from Cecil Price’s preface in the old Collins edition of Wild Wales.

Price described Borrow’s book as “the most inspired guidebook ever written because it was compiled by a great artist who understood and respected his subject”.

He went on to say that Borrow “described landscapes and industrial works, mansions and mountains. Welsh heroes and poets had their places, and even the people to be met with on the highway were rendered with astonishing vigour”.

“All Borrow’s art, his insight, keenness of observation and feeling for human destiny, were used to give his readers an affectionate interpretation of the Welsh and their history,” he added.

Starting in Llangollen in 1854, Borrow walked west and south, visiting places as far apart as Beddgelert, Bala, Dinas Mawwdwy, Devil’s Bridge, Tregaron, Strata Florida, Machynlleth and many more places besides.

Although Wild Wales was not the first travel book about Wales, it was the first to appeal to the mass market, and it continues to attract the same interest today.

To give a little information about Borrow and his background, this edition of Wild Wales has an introductory chapter about the man himself.

It explains that he was born in 1803 at Dumpling Green, near Dereham, Norfolk, “the second son of Cornishman, Captain Thomas Borrow, adjutant of the West Norfolk Militia”.

It goes on: “Throughout his childhood, the constant posting of the militia to various stations in both Britain and Ireland meant that the young Borrow became accustomed to a nomadic lifestyle.”

He carved a career as a writer in London and obtained regular employment with the British and Foreign Bible Society where he had the opportunity to practise his linguistic skills and to travel extensively.

This experience stood him in good stead, no doubt, for the long walking tours he would go on to take in Scotland, Wales, Ireland, Cornwall and the Isle of Man.

Interestingly, of these tours, only the Welsh one yielded a book. Wild Wales was the result, published in 1862.

But the tour itself took place eight years before that.

Borrow set off from Llangollen in 1854 and the journey he describes is fascinating.

Looking at places familiar to me and to you, our readers based in our edition areas across Ceredigion, Gwynedd and Powys, is of particular interest.

Chapter XLVI (46) lands the reader in Beddgelert. Conveying the area for his readers, Borrow said it “is situated in a valley surrounded by huge hills, the most remarkable of which are Moel Hebog and Cerrig Llan; the former fences it on the south, and the latter, which is quite black and nearly perpendicular, on the east. A small stream rushes through the valley, and sallies forth by a pass at its south-eastern end”. He goes on to relate the story of how Beddgelert got its name. Such information is easily found online today but not in Borrow’s time. It is easy to see why this book became so popular.

For those who are not familiar with the tragic tale of Gelert the dog, have a look at Wild Wales for Borrow’s account of the story.

He was moved by the experience of visiting the place said to be the tomb of the dog. Borrow said: “Who is there acquainted with the legend, whether he believes that the dog lies beneath those stones or not, can visit them without exclaiming with a sigh, “Poor Gelert!”

“After wandering about the valley for some time, and seeing a few of its wonders, I inquired my way for Festiniog, and set off for that place.

“The way to it is through the pass at the south-east end of the valley.

“Arrived at the entrance of the pass I turned round to look at the scenery I was leaving behind me; the view which presented itself to my eyes was very grand and beautiful.

“Before me lay the meadow of Gelert with the river flowing through it towards the pass. Beyond the meadow the Snowdon range; on the right the mighty Cerrig Llan; on the left the equally mighty, but not quite so precipitous, Hebog.

“Truly, the valley of Gelert is a wondrous valley – rivalling for grandeur and beauty any vale either in the Alps or Pyrenees.

“After a long and earnest view I turned round again and proceeded on my way.”

Borrow’s book not only brings the places he travels to life, but also the people he meets.

Take this account for example. Borrow writes: “I continued my way and came to a bridge, a little way beyond which I overtook two men, one of whom, an old fellow, held a very long whip in his hand, and the other, a much younger man with a cap on his head, led a horse.

“When I came up the old fellow took off his hat to me, and I forthwith entered into conversation with him.

“I soon gathered from him that he was a horsedealer from Bala, and that he had been out on the road with his servant to break a horse.

“I astonished the old man with my knowledge of Welsh and horses, and learned from him – for conceiving I was one of the right sort, he was very communicative – two or three curious particulars connected with the Welsh mode of breaking horses.

“Discourse shortened the way to both of us, and we were soon in Bala.

“In the middle of the town he pointed to a large old-fashioned house on the right hand, at the bottom of a little square, and said, ‘Your honour was just asking me about an inn. That is the best inn in Wales, and if your honour is as good a judge of an inn as of a horse, I think you will say so when you leave it. Prydnawn da ‘chwi!’”

Borrow’s journey took him far and wide through what we know now as Gwynedd, but he also ventured to places familiar to readers in what we know now as Ceredigion and Powys.

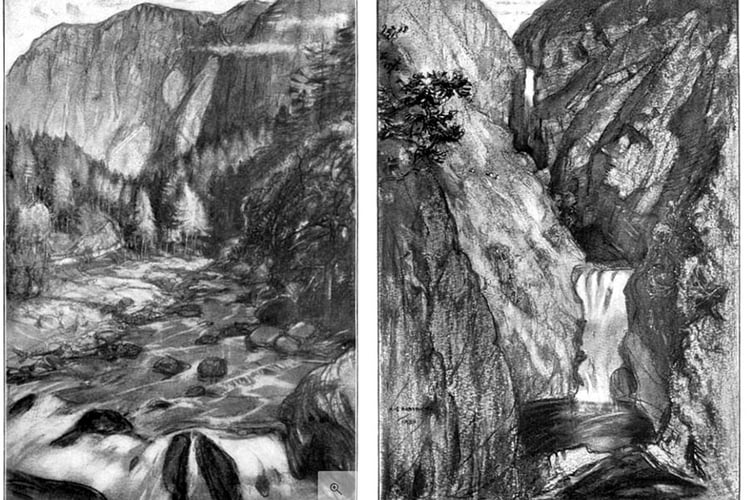

Borrow had great fun finding, and visiting, Devil’s Bridge. He enquired as to how he got its name and heard many a tale in a tavern before journeying to see the site for himself.

However, the bridge was not as obvious to tourists as it is today. Borrow said: “But where is the bridge, the celebrated bridge of the evil Man?

“From the bottom of the first flight of steps leading down into the hollow you see a modern looking bridge, bestriding a deep chasm or cleft to the south-east, near the top of the dingle of the Monks’ River; over it lies the road to Ponterwyd.

“That, however, is not the Devil’s Bridge; but about twenty feet below that bridge, and completely overhung by it, don’t you see a shadowy, spectral object, something like a bow, which likewise bestrides the chasm? You do!

“Well, that shadowy, spectral object is the celebrated Devil’s Bridge, or, as the timorous peasants of the locality call it, the Pont y Gŵr Drwg.

“It is now merely preserved as an object of curiosity, the bridge above being alone used for transit, and is quite inaccessible except to birds and the climbing wicked boys of the neighbourhood, who sometimes at the risk of their lives contrive to get upon it from the frightfully steep northern bank, and snatch a fearful joy, as, whilst lying on their bellies, they poke their heads over its sides worn by age, without parapet to prevent them from falling into the horrid gulf below.

“But from the steps in the hollow the view of the Devil’s Bridge, and likewise of the cleft, is very slight and unsatisfactory.

“To view it properly, and the wonders connected with it, you must pass over the bridge above it, and descend a precipitous dingle on the eastern side till you come to a small platform in a crag.

“Below you now is a frightful cavity, at the bottom of which the waters of the Monks’ River, which comes tumbling from a glen to the east, whirl, boil, and hiss in a horrid pot or cauldron, called in the language of the country Twll yn y graig, or the hole in the rock, in a manner truly tremendous.”

Strata Florida is described by Borrow, who said: “I turned to the east by a dung-hill, up a narrow lane parallel with the river.

“After proceeding a mile up the lane, amidst trees and copses, and crossing a little brook, which runs into the Teivi, out of which I drank, I saw before me in the midst of a field, in which were tombstones and broken ruins, a rustic-looking church; a farmhouse stood near it, in the garden of which stood the framework of a large gateway.

“I crossed over into the churchyard, ascended a green mound, and looked about me.

“I was now in the very midst of the Monachlog Ystrad Flur, the celebrated monastery of Strata Florida, to which in old times Popish pilgrims from all parts of the world repaired.

“The scene was solemn and impressive: on the north side of the river a large bulky hill looked down upon the ruins and the church, and on the south side, some way behind the farm-house, was another which did the same.

“Rugged mountains formed the background of the valley to the east, down from which came murmuring the fleet but shallow Teivi.

“Such is the scenery which surrounds what remains of Strata Florida: those scanty broken ruins compose all which remains of that celebrated monastery, in which saints and mitred abbots were buried, and in which, or in whose precincts, was buried Dafydd Ab Gwilym, the greatest genius of the Cimbric race and one of the first poets of the world.”

Of “Machynlleth, pronounced Machuncleth”, Borrow said: “It is situated in nearly the centre of the valley of the Dyfi, amidst pleasant green meadows, having to the north the river, from which, however, it is separated by a gentle hill.

“It possesses a stately church, parts of which are of considerable antiquity, and one or two good streets.

“It is a thoroughly Welsh town, and the inhabitants, who amount in number to about four thousand, speak the ancient British language with considerable purity.

“Machynlleth has been the scene of remarkable events, and is connected with remarkable names, some of which have rung through the world.

“At Machynlleth, in 1402, Owen Glendower, after several brilliant victories over the English, held a parliament in a house which is yet to be seen in the Eastern Street, and was formally crowned King of Wales.”

Borrow seemed to delight in his tour of Wales and, as mentioned earlier, it was the only one of his tours to be turned into a book. Wild Wales is the result and, 160 years after it was first released, it still makes for a compelling read.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.