In the early hours of the morning Mick woke up his wife Jenny to climb out the window of their cottage on 9 June, 2012.

Unable to sleep, he had watched the water rise from the Leri river that banks his home to swamp his lounge in 40 minutes.

The water rose so quickly that by the time they got down the stairs, they couldn’t open the frontdoor - rising seven feet, washing away their possessions, even their shed, and caking their family home of 40 years in silt and debris.

Watching their house flood from the pub, Mick Fothergill, 76, said: “It’s hard to explain the feeling of hopelessness, helplessness and disbelief that it’s happening to you.

“I’d never seen anything like it.”

Mick and Jenny Fothergill’s home was one of 27 houses in Talybont, Ceredigion, impacted by a flash flood which saw a month's worth of rain come down in 24 hours: “Just about everything of any value downstairs was destroyed.

“It was as if somebody had picked up the house and shaken it, covered it in mud and turned it upside down. It was devastating.”

Fourteen years later, the village is still at the same risk of flooding, with no large-scale prevention measures put in place, but climate scientists forecast flood risks will increase as the weather becomes wetter, windier, and more extreme.

Over the last decade, Wales has experienced increased flooding due to heavy rainfall, higher river flows, and sea surges. Currently, over 245,000 properties in Wales are at risk of flooding.

With no government help, the Talybont Floodees (as they came to be known) took up their shovels to do something about it themselves.

Every week in winter for the last five years, the group has climbed the hills above the village in wind, rain and snow to plant 40,000 trees to slow the flow of water down the valley.

They hope the trees will absorb the rainwater further up the valley to prevent sudden “peaks”, as Mick explained: “Our river is very reactive - it spikes very quickly and declines very quickly too.

“Our idea was that if we could reduce the peak we wouldn’t experience a flood to the houses, the river would just be active for a little longer.

“The planting, of course has a whole range of benefits - it’s not just water retention and trying to alter the hydrology, it helps biodiversity and all sorts of other things, so it’s great.”

For the group, waiting for the authorities to do something wasn’t an option, as the threat of losing their homes again rose with the river, and with it their anxiety every day of heavy rain.

Spearheaded by Talybont flood victim, Linda Denton, the group engaged landowners on four different sites and just before Christmas began this season's work to plant another 12,000 trees, having already created leaky dams using willow to hold excess water in periods of sudden downpours.

The group is made up of 15 to 75-year-olds, Talybont flood victims, their siblings, neighbours, students, residents from neighbouring villages and landowners, all working shoulder to shoulder.

David (Dai) Dowsett from Talybont saw firsthand the damage of the flood, housing his sister Jenny and Mick for the 11 months they were out of their home.

The 75-year-old estimates that he’s responsible for planting 2-3,000 trees: “The village came together and helped a lot of people in a lot of different ways.

“We came to understand that planting trees would help slow down floodwater and stabilise the ground.

“It also creates tree lines for birds and wildlife corridors for animals linking up to other tree plantations…

“When you’re inside, it’s easy to just stay in and watch TV, so it’s a good excuse to get outside.

“It’s something which I hope will have a long-term impact in slowing down the degradation of the valley.”

These interventions may seem small, but they can’t come quickly enough, according to the weather.

Autumn 2025 was the 10th wettest in Wales since records began almost 200 years ago, with November’s rainfall 59 per cent above average.

The flooding before Christmas created more homelessness in Monmouth, Neath Port Talbot, and Tenby, with more extreme weather set to come.

In this context, it’s hard to see tree planting as little more than a sticking plaster for the country’s weather problems, but the group would disagree with you.

According to the Woodland Trust, which provides the native trees and funds a volunteer coordinator for the group, the trees help absorb water deeper into the soil through their roots, as opposed to running off the surface and into rivers at high speed, reducing surface run-off by 80 per cent compared to asphalt.

The leaves also help, with studies finding up to 30 per cent of rainfall is evaporated from leaves without ever reaching the ground.

Reducing flood risks takes a village, as farmer Rhodri Lloyd-Williams discovered: “[Planting trees] is a hard job and a long slog, so it was confusing when people said they wanted to help.

“I thought, ‘you’re mad’!

“But people turn up twice a week, everyone’s chatting and stopping for cakes and tea breaks.

“Quite often you’ll find you’re working shoulder to shoulder with people who may have never set foot on a livestock farm before.”

This winter, the volunteers are working 1,500ft above sea level at the Lloyd-Williams’ family farm, Moelgolomen.

The family started planting trees in 2018 “first and foremost as a farming decision”, after trialling rotational grazing with sectioned fields led to better yield of grass for his sheep and cattle, saving money on feed.

The grass was found to grow more with better root systems, thanks to healthier, less compacted soil - something that also helps absorb rainwater.

The 750 acres of rolling hills have been in his family since the 1700s, but Rhodri is hoping to futureproof the land for generations to come.

The 43-year-old father of three said: “I’d like to turn every fence in the farm into a double fence with a hedge.

“In 2018, the summer got up to 35 degrees Celsius, and we suddenly realised that we’ve got Welsh Black cows with no shelter on the hills.

“I needed to think about shelter from the dry summers and the cold, wet winters we’re having.”

But he said that the volunteers aren’t just helping boost the number of trees they can plant in a day, sharing the story of a volunteer tree-planter and dedicated vegan buying beef from him after learning about how he runs his farm: “It’s great because you don’t always get the opportunity to talk to each other, you get to hear other views.”

Together with the volunteers, the farm will this year achieve planting over 100,000 trees, to which Rhodri said: “A hydrologist said we’d need to plant over two million trees to make a difference to flood risk, and suggested it was pretty unrealistic.

“But we’ve already planted 90,000 trees, and we’re just one farm, so actually we’re talking about 20 times what we’ve done, so it’s not beyond the realms if we keep going.”

Ultimately, however, it does cost them money, and Rhodri said their goal would be a lot more achievable with government support: “I dream of a future where the government or perhaps private equity made it so that it was at the very least cost neutral for us, ideally with some sort of incentive to make other farms jump on the bandwagon.”

Dai agrees projects like this need both “community and government involvement”: “Planning permission and financial help are obviously necessary.

“It would be useful if the government were more proactive in explaining why [tree planting] needs to be done; there are already negative reactions from some parts of the community about tree planting.”

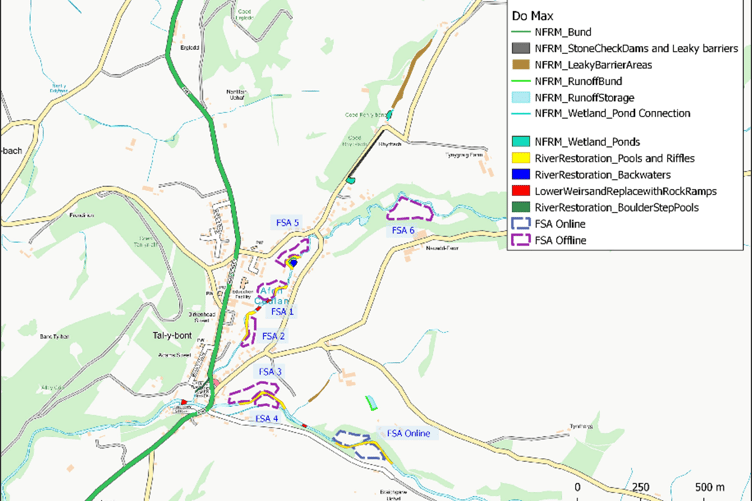

In 2025, Ceredigion County Council presented the community with options to address flood risk in the village, but created without community involvement, according to Mick.

The 600-strong village, which is the meeting place of the rivers Ceulan and Leri, had in that time created their own Community Flood Plan with self-appointed emergency responders, mapped the catchment to better understand what happened that fateful day, conducted citizen science surveys of water quality for sewage pollution and soil contamination, and set up a successful tree planting group, on top of tackling their own issues of temporary homelessness, insurance battles and the emotional upheaval that comes with losing a home.

Ceredigion County Council said it “recognises and welcomes the significant efforts” made by the Talybont community, and that numerous modelling exercises and detailed technical studies had been done to understand why flooding occurs there during extreme events and identify the most effective long-term solution.

The Welsh government said that it promotes natural flood management, including expanding wetland and woodland habitats, having invested £377 million to reduce flood risks since 2021.

A spokesperson added: “It is more important than ever that we continue to protect our communities from the threats of climate change, and managing the increasing risks of flooding remains a priority for us and our flood risk management authorities.”

Only this month, the protest-hit Sustainable Farming Scheme launched - the first Welsh scheme of its kind since Brexit - intending to make it easier for farmers like Rhodri to advance green initiatives on their land.

The Floodees have shown remarkable resourcefulness and resilience in their work to save their village, but it begs the question - should they have been left to do it alone?

Currently, half of all councils in Wales (11 of 22) are doing emergency repairs to flood defences.

With squeezed budgets, councils are prioritising the areas most in need of intervention; however with weather getting worse, residents across flood-striken Wales are asking whether more needs to be done as prevention.

In 2018, a man in Carmarthenshire lost his life due to flooding, whilst it has killed thousands in India in recent years, and hundreds in Germany.

The Met Office classifies the UK as 7 per cent wetter than 60 years ago, thanks to climate change causing more frequent, heavy rain events.

.png?trim=0,0,1,0&width=752&height=500&crop=752:500)

Whilst Talybont awaits the council's flood alleviation scheme, and without the resources of a government, the Floodees turned to natural flood management methods as an accessible way to change the landscape of their valley; methods which span from tree planting to reintroducing beavers, and restoring peat bogs that act as “giant sponges” for the landscape.

They have achieved the difficult task of mass buy-in from the community, including landowners who can make or break a scheme that, without the backing of authorities, hinges on access to land and the agreement of those who own it.

However, as Friends of the Earth Cymru put it, the “scale of floods in the future will be determined by governments' policies and actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to slow climate change”.

As the water receded the next day in 2012, the Fothergills moved their belongings onto the street, neighbours carefully hung photos from the Fothergill’s old family albums in their greenhouses to dry, and residents from neighbouring villages brought food so that every day the Talybont Floodees could gather for a community-made feast in the pub as they compared notes on insurance claims, how to wipe down clay from walls and what to do next.

.png?width=752&height=500&crop=752:500)

The Floodees met every day, then every week, then every month for many years, equipping themselves with the knowledge of why it happened and creating a plan of how they could stop it from happening again.

Mick said: “It’s easy to look at the valley and say, wow, it’s beautiful.

“When you look at the landscape properly, you develop an understanding of how it’s changed to either benefit or hinder the hydrology, and perhaps how we can use it.

“It teaches you to appreciate where we live in a different way.

“[The tree planting] brings people together, it bonds us together.

“People come from different walks of life, and everyone has a common goal - to plant.

“We have picnics up there.

“It’s hard work, but a lot of fun.”

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.